In about 17,000 square feet of exhibits, including the brick wall that absorbed bullets aimed at seven mobsters in Chicago's infamous 1929 St. Valentine's Day Massacre, the museum attempts to tell "both sides of the story" of organized crime in America, and how it came to shape Las Vegas.

The stately downtown building that houses the museum was part of that story. A former federal courthouse, it was one of 14 sites for the 1950-51 Kefauver Committee hearings, a Senate investigation into the mob and its influence on the nation's economic, political and cultural life.

At the entrance to the repurposed site, a black and white photo half the size of a billboard hangs to the left. It's of a toe, with a white tag. The tag reads: "Homicide. Benjamin Siegel. 810 Linden. Beverly Hills."

That would be "Bugsy" Siegel, the gangster figure familiar to many through Warren Beatty's portrayal of him in the 1991 film, "Bugsy,"

about the mob's role in the birth of the Las Vegas Strip.

So begins the journey the Mob Museum takes visitors on, an arc from the 1930s to the 1980s, when organized crime was defined by family and ethnic affiliation, and law enforcement and the justice system evolved as institutions focused on curbing its influences.

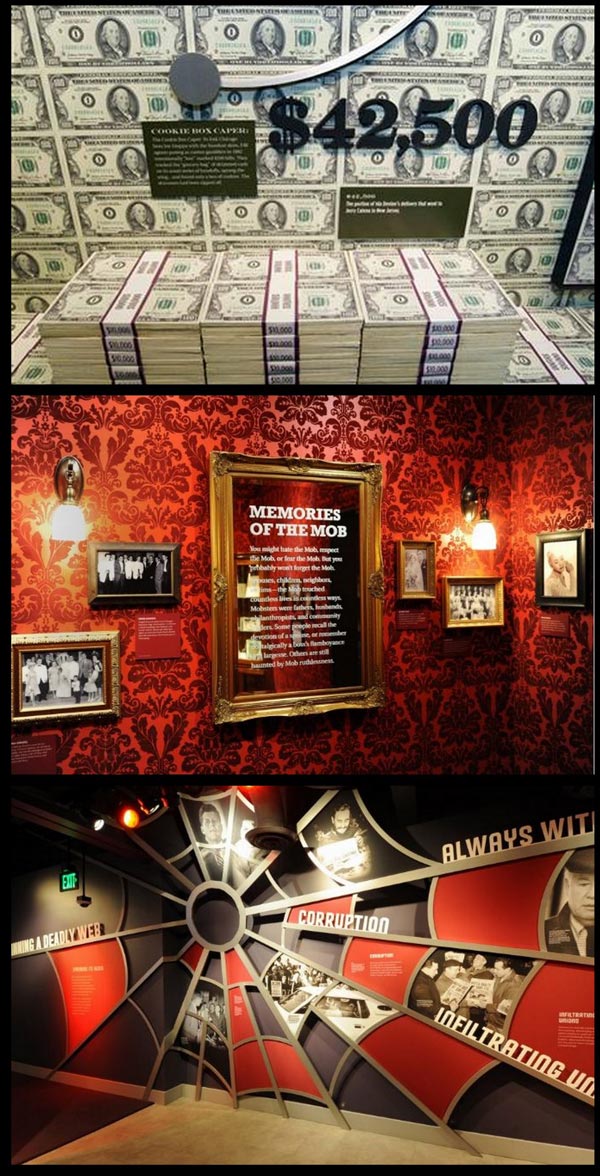

Along the way are displays of Prohibition-era whiskey flasks and Kennedy-era FBI wiretaps. There is also a page from Meyer Lansky's accounting ledger and suits worn by fictional HBO mob boss Tony Soprano.

One section explains the "Web of Deceit" woven by the mob in its heyday, influencing U.S. national elections and Cuba's Fidel Castro.

The courtroom where the Kefauver hearings took place has been restored, complete with the original wooden benches from the hearing room and a film that takes visitors back to 1950.

Curator Kathleen Hickey Barrie and her husband, Dennis Barrie, developed the museum's exhibits. The two have long careers that include working on the International Spy Museum in Washington.

Hickey Barrie said locating the museum in Las Vegas was an obvious choice. "Having it here makes it more interesting than if it was in New York or Chicago, two places it easily could have been. Here is where you have this turn in history from bootlegging to mobsters creating places that people from all over the world wanted to come to," she said. "It is about Las Vegas, but I really think it's a national story," Hickey Barrie added.

The idea for the museum originated with Oscar Goodman, who made a national name for himself -- and a fortune -- as a defense attorney for Meyer Lansky, Tony Spilotro and other figures from the world of organized crime.

As mayor of Las Vegas from 1999 to 2011, Goodman often appeared at official events with a martini glass in one hand and a showgirl hanging off each arm. His City Hall office overlooked the former courthouse where he had once argued on behalf of his notorious clients.

Goodman, like the museum, and like Las Vegas itself, could easily be taken as a bizarre, sensational lark. But historian Michael Green, who served as a consultant on the project, says that would be a mistake.

"Ideally," he said, "the museum will help people understand better where Las Vegas comes from, and where they come from." At the same time, he allowed, "They'll also go away thinking, 'Only in Las Vegas could there be a museum like this.'"